In Exegesis posts, I project my own ideas onto popular art—mainly fiction, music, and film—with little regard for the artist’s intentions. Past subjects include Tarkovsky’s Stalker and Funkadelic’s Maggot Brain. Future subjects will include Octavia Butler’s Earthseed Series, the music of Dan Deacon, and TV’s Adventure Time.

Typically these posts are a thank you for paid subscribers, but af Klint’s work deserves more attention, so I’m pushing the paywall to the bottom.

Hilma af Klint was arguably the first Western painter to experiment with abstraction, a style that dominated the the first half of the 20th Century. Though her work was ignored for decades, she’s now recognized as a pioneer of the genre.

af Klint’s paintings were inspired by two countercultural, female-dominated religious movements: Spiritualism and Theosophy. She claimed the so-called High Masters—a group of enlightened, etheric beings—had instructed her to paint, and guided her hand as she channeled their message to humanity.

My mission, if it succeeds, is of great significance to humankind. For I am able to describe the path of the soul from the beginning of the spectacle of life to its end.

—Hilma af Klint

With af Klint, it’s often hard to distinguish art from prophesy, or genius from insanity. But the work itself holds a power that’s impossible to ignore.

Outline

Pioneer

For decades, af Klint’s work was mostly overlooked—especially in comparison to contemporaries like Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian. New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), a self-appointed authority on the historical narrative of abstract painting, has repeatedly snubbed her. But a 2018 exhibition at The Guggenheim brought her out of obscurity, drawing more visitors than any other attraction in the museum’s 80 year history.

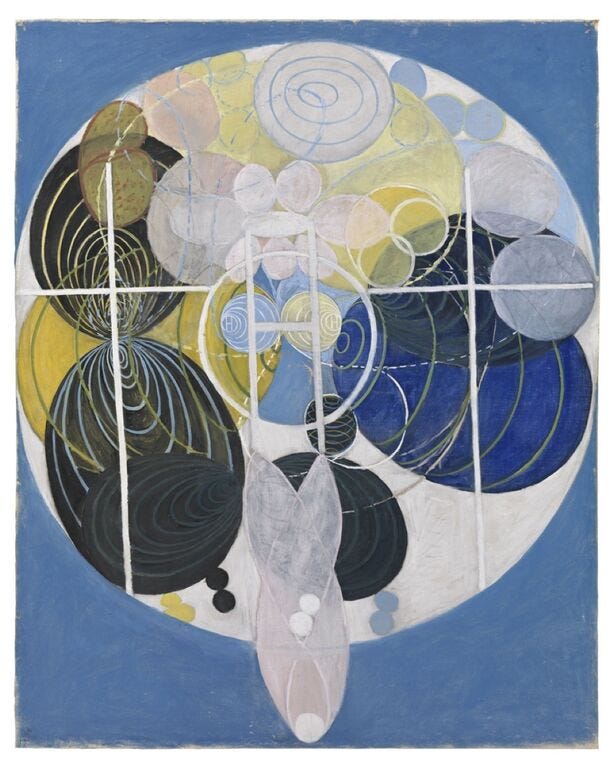

Meanwhile, MoMA’s 2012 Inventing Abstraction exhibit completely ignored af Klint. It featured paintings from 1910 onward, crediting Kandinsky with inventing the genre in 1911. af Klint panted this in 1907:

In fact, her work often prefigures later paintings by more famous artists:

Interestingly, Kandinsky and af Klint shared a connection via the esotericist Rudolf Steiner. He had recently viewed af Klint’s work when he met with Kandinsky in 1908—whether Steiner shared his photographs with Kandinsky is a question that will likely plague art historians for decades.1 Kandinsky and af Klint’s shared interest in Theosophy could easily account for a contemporaneous discovery of abstraction, but the timing of Steiner’s visit is intriguing.

Spirit in Nature

Nature figures heavily in af Klint’s work. Before entering art school she would often paint detailed illustrations of local flowers; later she would earn a meager living documenting the dissected tissues of large animals.

Much like Steiner, whom she idolized, af Klint saw plants as a living doorway to the spiritual world. In her notebooks, one drawing of an aspen tree is labeled with “Obedience. Humility.”; another captions an apple tree with “Enlighten me about my thoughts. Arrogance. Help me improve the spleen (and liver) of humanity.”

Behind the effervescent force of a plant is concealed the warmth of feeling.

—Hilma af Klint

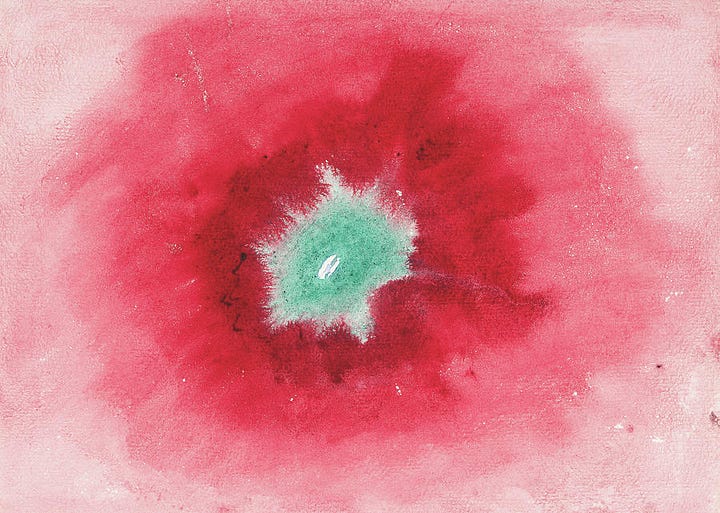

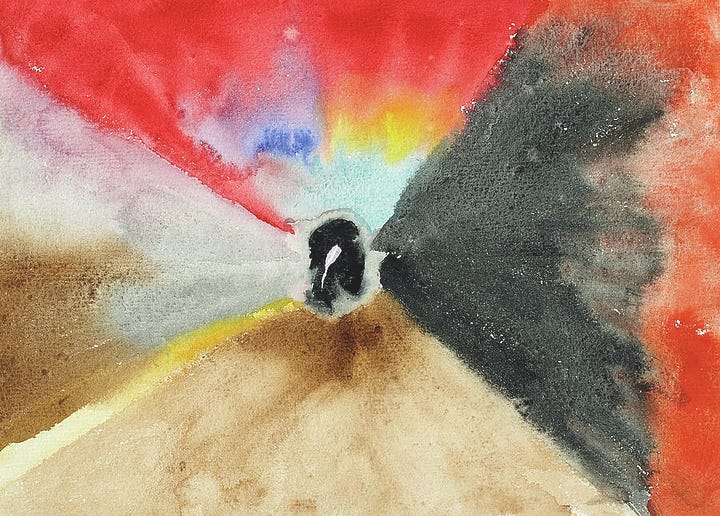

These themes are explored in a series of 70 watercolors: On the Viewing of Flowers and Trees:

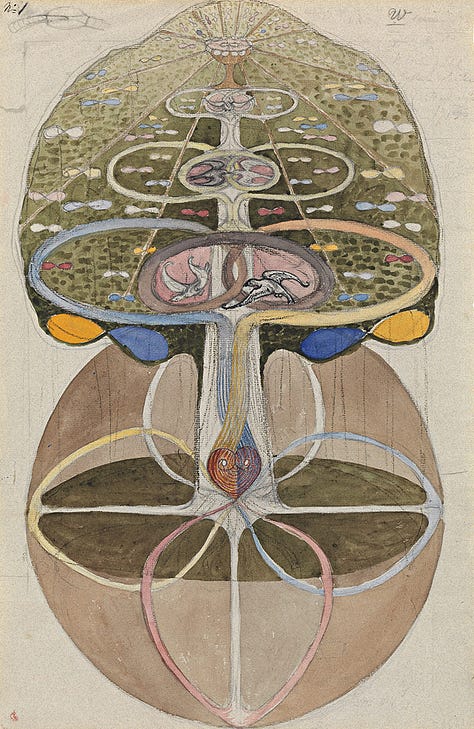

The connection between human and vegetal life comes to the foreground in another series entitled The Tree of Knowledge; the paintings all depict a transcendent whole emerging from plantlike forms.

That feeling of kinship with plants is a topic we’ve discussed before; it seems to be a common theme among mystics and naturalists.

The Invisible World

It’s easy to poke fun at Spiritualism. Its attempts to commune with the dead, to see the future, to channel “High Masters”, might seem to us like Ouija board antics.

But it’s important to understand the historical and scientific context in which Spiritualism flourished. Science had only recently moved beyond taxonomies of visible, macroscopic phenomena; suddenly we were discovering hidden worlds of electromagnetic waves, germs, atoms, and sub-atomic particles.

Emerging technologies—radio, photography, artificial light, audio recording, telephones—made magic a reality. The public’s imagination was dizzied with possibility.

If telephones could allow voices to speak over long distances, why couldn’t the living speak to the dead?

—Catharine de Zegher, via Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future

And the divorce of science and religion, though well underway, had not yet fully materialized. Many prominent scientists, engineers, and academics were convinced that a sober approach to spiritualism could bridge the emerging gap; they earnestly engaged in psychical research.

af Klint was an eager participant. From 1896 until 1908, she belonged to a small group of women—known as The Five—who made regular attempts to contact other-worldly life forms, living beyond the veil of mundane reality. They believed these beings surrounded and suffused the waking world, constantly inviting us to communicate and participate.

Those granted the gift of seeing more deeply can see beyond form, and concentrate on the wondrous aspect hiding behind every form, which is called life.

—Hilma af Klint

The Five experimented with prayer, seance, trance, and of course, automatic drawing. These practices would go on to fuel af Klint’s shift into abstraction: in 1904 she channeled a message about “astral paintings” from an etheric being named Ananda. Two years later, his peer Amaliel commissioned a series, Primordial Chaos; she and her group (especially Anna Cassel) then collaborated to produce some of the earliest works of Western abstraction:

Whether af Klint deserves full or partial credit for this series is up for debate. It seems she had a tendency to over-assert herself with respect to The Five; the group disbanded in 1908 after she channeled a message that she was meant to be its leader.

The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings, and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brush stroke.

—Hilma af Klint

After the group’s disbanding, she continued to paint for decades, producing over 1000 works of non-figurative art.

The Geometry of Religion

While af Klint put some of her thoughts in writing, abstract painting served as a vehicle for ideas that were difficult or impossible to express in words or in figurative art. Over time, she developed an intricate vocabulary of geometry and color.

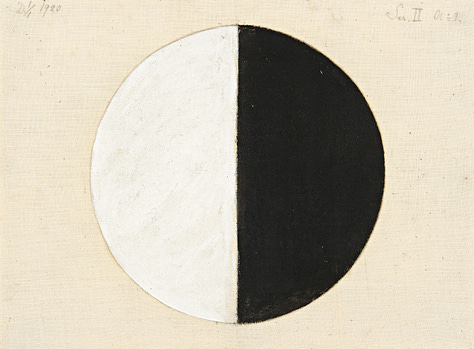

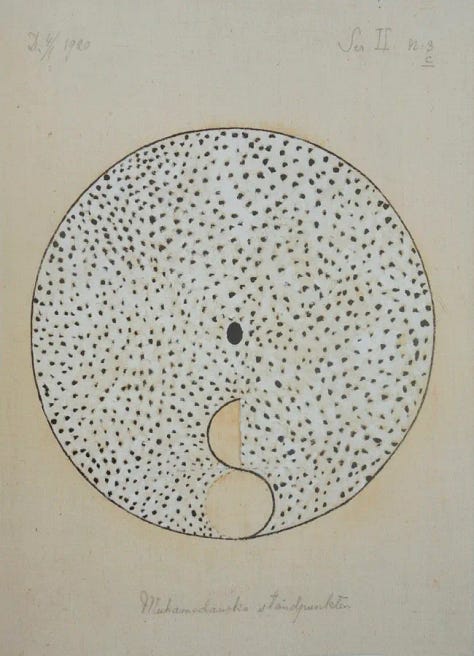

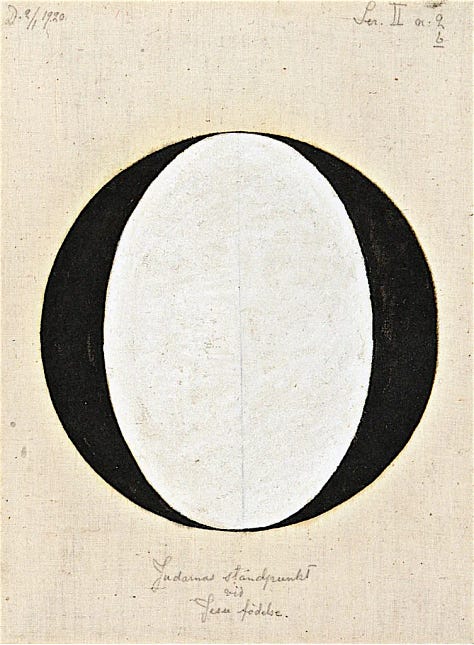

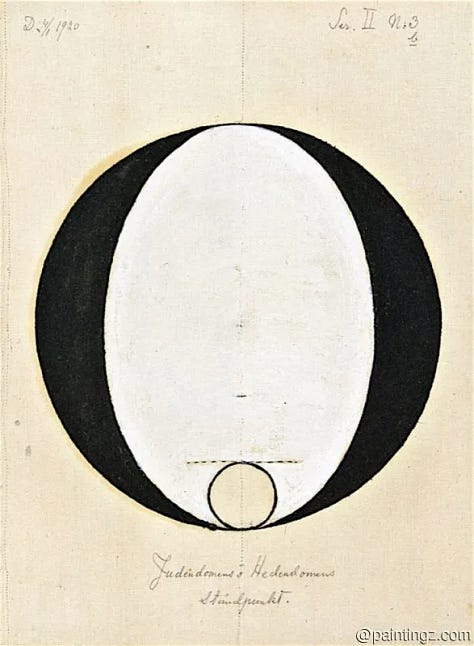

An example: around 1920 she painted a series on the standpoints of various religions. The series begins with a circle divided horizontally, with black and white halves. She then distorts this picture in various ways to illustrate the differences between spiritual philosophies.

I suspect these paintings (along with several others) were inspired by the Taoist Yin-Yang symbol (which would have been well known to Theosophers)—the interplay of opposites is a constant theme in af Klint’s work. And while I could happily speculate2 about the intent behind her depictions of Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, and Islam, I doubt any single interpretation could capture exactly what she saw.

Even more fascinating are her depictions of what I’ll call moral inversion. My favorite in this series shows a cross in the top half of the canvas, surrounded by black-and-white geometry; the shapes are reflected in the bottom half of the canvas—including the occult inverted cross—but with a rainbow of colors.

In the top half, it’s easy to see af Klint’s frustration with the mainstream Christian philosophy surrounding her; she spent a great deal of time exploring Christianity’s more esoteric emanations, presumably represented by the bottom half of the image. And while the association of rainbows with the LGBTQ community wouldn’t come for several more decades, af Klint—a gender nonconformist and probably a lesbian—is clearly using it to contrast the black-and-white worldview of the dominant culture.

Importantly, neither half of the image is glorified or vilified—instead, they bleed into one another. For af Klint, transcendence takes the form of two opposites joining into a greater whole.

The Illusion of Gender

Many who fight in this drama are dressed in the wrong clothing. Many female costumes conceal a man. Many male costumes conceal the woman.

—Hilma af Klint, Studies of the Life of the Soul

Gender figures heavily in af Klint’s work, and was a constant source of friction in her career. The idea of female artists was a fairly new one—The Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts, where she received formal training, had only begun admitting women 18 years prior; many male artists vocally opposed the idea of women joining their ranks.

But af Klint’s work isn’t a simple rejection of patriarchy—it portrays masculinity and femininity as opposites seeking to reunite. Much like the artwork of medieval alchemy or the drawings of Carl Jung, her paintings depict hermaphroditic forms, or male and female bodies coalescing into a whole.

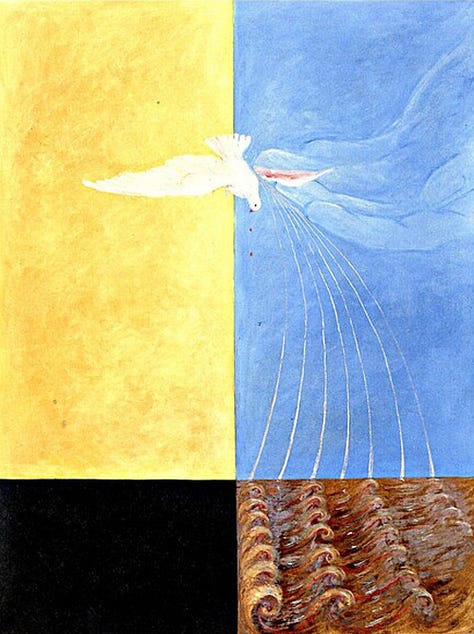

This theme becomes even clearer in light of the visual vocabulary she outlines in her notebooks. Femininity and masculinity are represented by pairs of symbols: blue and yellow, lily and rose, eyelet and hook, respectively; pink stands for spiritual love, and red for physical love; the spiral (often in the form of a snail shell) represents evolution; the swan, one of her most important symbols, stands for the union of opposites, apotheosis, transcendence.

Transcendence

Nearly all of af Klint’s paintings, either individually or in series, deal with the themes of growth and transcendence.

You are bewildered by what we have told you, but the phenomenon we are trying to explain is truly bewildering. What is this phenomenon, you ask? Well, beloved, it is the phenomenon of secret growing.

—Hilma af Klint

It’s this fact that allows me to see past the fantastical imagery of Spiritualism, and into the core of af Klint’s message. It’s the same message of medieval alchemy, of Taoist philosophy, and the message which Carl Jung tried in vain to distill from religious superstition. They all push us down the same path: we look inward, discover an abundance of possibility, resolve internal contradictions, and grow beyond them.

In this moment, I’m aware, living as I do in this world, that I am an atom in the universe possessing infinite possibilities of development, and I want to explore these possibilities.

—Hilma af Klint

If I reframe af Klint’s “High Masters” as dream characters or tulpas, as products of her subconscious mind, it’s much easier for me to see the source of inspiration in her work. af Klint’s depth of imagination and creativity are clear evidence that she did connect to a vast, hidden world full of wisdom—even if that world was embodied within the confines of her own skull.

af Klint was convinced her work was an important message for humanity, and believed it was meant to be exhibited in a grand, spiral temple—an echo of the helices and snail shells that dominate her work. 193 of her paintings were specifically created to adorn this temple, including three incredible altarpieces:

She never managed to get her spiral temple built, but nearly a century later, her work was featured in Frank Lloyd Wright’s wonderfully impressive six-story spiral: The Guggenheim Museum.

Whether this was a miraculous act of prophesy from af Klint, or a clever connection made by an enterprising Guggenheim curator, depends on your perspective. But the exhibition broke attendance records and brought af Klint’s work into the spotlight. It’s a beautiful, synchronistic conclusion to af Klint’s obscurity, and a hopeful beginning to a new narrative on the origins of abstract art.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Superb Owl to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.