Time is a Wheel, Time is an Arrow

Linear and cyclical views of time have competed for millennia

We tend to think of time as an arrow: A leads to B leads to C. Linear time undergirds our understanding of causality, and makes it easy to construct narratives that have a beginning, middle, and end.

But it’s also an historically uncommon view. Most pre-modern cultures thought of time as a wheel, with cycles that recur over days, years, and centuries. This created a wildly different relationship with the world and an altered sense of self.

Both metaphors have merit. But our bias for the linear view has infected everything from physics to mental health. How did we get here, and what can we do to find balance?

Outline

Time as a Worldview

Pre-Modern Cultures

You have noticed that everything an Indian does is in a circle, and that is because the Power of the World always works in circles, and everything tries to be round…The sky is round, and I have heard that the earth is round like a ball, and so are all the stars. The wind, in its greatest power, whirls. Birds make their nests in circles, for theirs is the same religion as ours. The sun comes forth and goes down again in a circle. The moon does the same, and both are round. Even the seasons form a great circle in their changing, and always come back again to where they were. The life of a man is a circle from childhood to childhood, and so it is in everything where power moves.

—Black Elk (emphasis mine)

Circles dominate the pre-modern experience of time. Nearly every natural manifestation of time comes in cycles: day and night, the motion of the planets, migratory patterns, the seasons. Pre-modern time-keeping systems are no different.

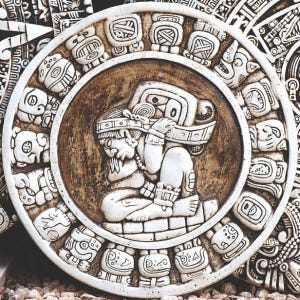

You might remember the 2012 apocalypse craze, which was fueled in large part by the Mayan calendar completing a 5,125 year cycle. New Agers interpreted this as the “end of time”, which might have made sense if the Mayans had used a rope to demarcate time. The whole point of a wheel is that it keeps turning.

Similar calendars, with cycles lasting many years, arose in Africa, Asia, and throughout Mesoamerica.

Hinduism has a particularly intricate cyclic calendar, with units of time ranging from microseconds to trillions of years. Even the cosmos itself is cyclical in Hinduism—each universe lasts for one kalpa, or 4.3 billion years. Other cosmic wheels of time can be found in Asian, Native American, and South American cultures.

Often these cultures equate different cycles with one another—day and night map to summer and winter, which in turn map to the repeated birth and death of the universe. In Hinduism, our kalpa is just 12 hours of Brahma’s time, followed by a 12 hour pralaya of destruction.

For the pre-modern person, daily life just doesn’t change much from year to year, or even century to century. The same rituals, hunting methods, and medicinal practices persist across generations. The universe is a song on repeat.

The notion that time is going somewhere would have seemed very strange.

Judeo-Christian Time

Something changed with Judeo-Christian mythology. In The Sacred and the Profane, historian Mircea Eliade writes:

…Judaism presents an innovation of the first importance. For Judaism, time has a beginning and will have an end. The idea of cyclic time is left behind. Yahweh no longer manifests himself in cosmic time (like the gods of other religions) but in a historical time, which is irreversible. Each new manifestation of Yahweh in history is no longer reducible to an earlier manifestation…

Christianity goes even further in valorizing historical time. Since God was incarnated, that is, since he took on a historically conditioned human existence, history acquires the possibility of being sanctified.

The events of Jewish and Christian mythology are (ostensibly) real historical events: the life of Abraham, the exodus from Egypt, the Crucifixion of Jesus. Any supposition that these events recur—especially the Crucifixion—is heresy.

While this probably wasn’t the first time humans considered the idea of linear history, Christianity’s wildly successful spread cemented it as the dominant worldview. As Europeans colonized the world, they systematically eradicated cyclical ideas of time in favor of Christian teleology: the world was created in seven days, and is heading towards a grand finale—believe it or die.

Progress and Singularity

The Christian notion of linear time took root in our imaginations, and persisted even as the world secularized. Eliade writes:

Hegel takes over the Judeo-Christian ideology and applies it to universal history in its totality: the universal spirit continually manifests itself in historical events and manifests itself only in historical events…The road is thus opened to the various forms of twentieth-century historicistic philosophies…historicism arises as a decomposition product of Christianity

For instance: Karl Marx, Hegel’s most famous disciple, built a cosmology in which humanity iterates its way to socialist utopia. He borrows the Judeo-Christian idea of history marching towards an inevitable conclusion, but rewrites the ending.

Linear historicism has only strengthened since Marx. Thinkers like Yuval Noah Harari, Francis Fukuyama, and Stephen Pinker write best-selling treatises on our moral, intellectual, and technological progress. They begin the story sometime around the dawn of civilization, and play it forward into eschatological singularity.

The only thing we actively debate is whether the road leads to utopia or dystopia. The idea that we’re going somewhere is almost too obvious to mention.

Cyclic Alternatives

Cyclic conceptions of history are rare these days. It’s hard to justify a cyclic theory when we’re surrounded by overwhelming technological change.

One recent bit of pseudoscience has at least tried to challenge this narrative: Graham Hancock’s Ancient Apocalypse. Hancock believes another advanced civilization dominated the world 10,000 years ago, but was wiped out by a global catastrophe. There’s very little evidence to support this, but it plays into a narrative of cyclical time: technological civilizations rise and fall, and ours might be no different. Hancock isn’t great at science, but he’s crafted a beautiful myth.

The Great Filter Hypothesis makes a similar, slightly more scientific claim. It confronts the Fermi Paradox, which asks why the universe, given its size, isn’t teeming with spacefaring aliens. One possibility: life is common, but technological civilizations tend to collapse before going interplanetary. Global warming and nuclear proliferation lend some frightening support to this theory.

The theme here is that we’re too fixated on a relatively small duration of time. Our window of observation is tiny on geologic or cosmic scales—thousands of years of growth could still be part of a much larger cycle.

How far back can we zoom out? Nietzsche is probably the most daring here. No surprise that the guy who wrote The Antichrist also argued against Judeo-Christian time.

In The Gay Science, Nietzsche revitalized the philosophy of cyclic time with his concept of Eternal Return.

What, if some day or night a demon were to…say to you: "This life as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live once more and innumerable times more; and there will be nothing new in it, but every pain and every joy and every thought and sigh and everything unutterably small or great in your life will have to return to you, all in the same succession and sequence—even this spider and this moonlight between the trees, and even this moment and I myself. The eternal hourglass of existence is turned upside down again and again, and you with it, speck of dust!"

For Nietzsche, in an infinite expanse of time, anything that can exist will exist, and it will exist an infinite number of times. This is an idea we’ve explored before through Georg Cantor and the Principle of Plenitude, and as we’ll see, it’s surprisingly well-grounded in physics.

The Physics of Time

Cosmology

You’ve probably heard of Big Bang Theory, the standard cosmological model taught in grade school. You may have also noticed that Big Bang cosmology echoes the Christian view of time: a sudden explosion of creation that eventually ends in “heat death”.

What you might not know is that it was first proposed and defended by a Catholic priest: Georges Lemaître.

At the time, most physicists—including Einstein—preferred a steady-state model of the universe, where everything is essentially eternal and homogenous in time. Some physicists, like Hoyle and Eddington, complained that Lemaître’s theory was religiously motivated.

Unfortunately for the atheists, steady state theory was eventually disproven, and supporting evidence for the Big Bang only grew. Astrophysicist Robert Jastrow describes their discomfort in God and the Astronomers:

The development is unexpected because science has had such extraordinary success in tracing the chain of cause and effect backward in time. For the scientist who has lived by his faith in the power of reason, the story ends like a bad dream. He has scaled the mountains of ignorance; he is about to conquer the highest peak; as he pulls himself over the final rock, he is greeted by a band of theologians who have been sitting there for centuries.

But Lemaître may not have the final word—cyclical cosmologies have begun to gain traction. Nobel laureate Roger Penrose is their greatest proponent: his Conformal Cyclic Cosmology is a solution to Einstein’s field equations which results in an unending chain of universes. And Penrose’s theory is only one in a large family of cyclic alternatives to the Big Bang.

Entropy and Recurrence

Entropy is frequently referred to as an “arrow of time”—disorder constantly increases, but rarely decreases. You’d never expect to shuffle a deck of cards and come out with a perfect ordering from aces to kings.

But with infinite time, things get weird. Perform enough shuffles, and you’ll eventually find your way back to a perfect ordering.

This is the idea behind Poincaré recurrence. Poincaré managed to prove that, in spite of entropy, dynamical systems (with some reasonable qualifications) will always return to their starting position (or arbitrarily close to it) over very long periods of time. Whether the universe as a whole is subject to this theorem is an open question, but Nietzsche would certainly argue in favor.

So while entropy gives time an arrow, it does nothing to prevent that arrow from eating its own tail.

Time in Practice

I predominantly experience time as an arrow—I think of my life as a progression of failures and accomplishments, accompanied by steady personal growth. Even in the short-term, I have a feeling of going somewhere: I think about what I want to get done this weekend, or what my next blog post will be about.

But the meat of my life is repetition: weekly meetings, quarterly deadlines; walking the dog, brushing my teeth; eating, sleeping, breathing. I spend most of my day doing things I did yesterday and will do again tomorrow.

Major events, like a promotion or marriage, can modulate these cycles. Some new habits might arise and others might fade. But the cycles themselves mostly persist.

I rarely notice these things as I scurry from one goal to the next. This is natural—we notice novelty while repetition fades into unconsciousness. I’m barely aware of stepping into the shower, unless the hot water is out.

Two things have helped me gain a more balanced perspective: ritual and meditation.

Ritual

Ritual is a simple method for tuning into the cyclic aspect of time. It doesn’t need to be anything sacred or goofy—it just needs to be conscious. Pooping can be a ritual if you do it right.

The goal isn’t to simply repeat a behavior—that’s an unconscious habit. Ritual is about repeating a mindstate: using routine to put yourself into an excited or thankful or pensive mood. Athletes have pregame rituals; couples have romantic rituals; warriors have pre- and post-battle rituals. Whatever the circumstances, we can use ritual to cultivate an appropriate inner state.

An example: several years ago, I began conjuring a sense of gratitude at the beginning and end of each day. To reinforce the feeling, I bow my head forward and mentally say “thank you”. The whole thing lasts about five seconds.

It’s a little silly, but the reward-to-effort ratio is off the charts.

Few things have improved my day-to-day mood more than this tiny gesture. It creates a mental anchor, a safe harbor I can return to no matter what happens during the day. On awful days, days where friends have died, I’ve found myself thinking “everything is different now, it’s all over, it’ll never be the same”—and yet I’m still able to return to this mindstate for respite.

Thanks to a little ritual, my wheel always returns to the same place.

Meditation

A common meditation instruction is to focus on your breath. My mind invariably ends up wandering into some linear narrative about politics or crypto or Elon Musk. But the more I manage to focus on my breath, the more time starts to feel strangely cyclical. Each breath is almost identical.

When I’m able to really focus, I tune into other bodily rhythms—I feel not only my heart beating, but the systole and diastole of its pulse throughout my body. Sometimes I’ll start to feel a vibration of around 4-8 Hz in my head and hands, which I imagine might be my nervous system chittering away—and vibration is just a rapid cycle.

Most meditation methods are designed to induce this sense of periodicity. Repeating mantras, breathing exercises, shamanic drumming, physically rocking back and forth—the repetition tunes you into the cyclicality of time.

Occasionally, I’ll be struck by a sense of déjà vu as I meditate my way into a mindstate that’s identical (or nearly identical) to something I’ve felt in the past. This experience creates a sense of repetition not just between breaths, but between days, months, and years.

A Matter of Perspective

I was tempted to title this post “Time is a Wheel, not an Arrow”. We’re strongly biased towards the linear view, especially at the macro level. We see our lives and our civilization progressing toward some indeterminate end-state. I want to pull in the opposite direction.

But both the linear and the cyclical view of time have merit.

A purely linear view of time is exhausting. There is a perpetual sense of forward motion, with no rest. In a perfectly linear world, none of us would sleep or eat—we’d just work our way towards entropic death. But a linear view definitely gets shit done.

The cyclical view grounds us in history and keeps us balanced. It reminds us that the best things—friendship, food, sleep, sex—are timeless. But a purely cyclical view can lead to apathy, nihilism, and despair—why do anything if we’ll just end up back in the same place? As Eliade puts it:

…when it is desacralized, cyclic time becomes terrifying; it is seen as a circle forever turning on itself, repeating itself to infinity…

Properly balanced, the two viewpoints synthesize into a paradoxical but powerful state of mind: we can have ambition with equanimity, and progress with stability. Thankfully, the cyclic view is reemerging after centuries of obscurity.

I just hope we don’t overcorrect.

Great post as always, Mr. Owl. Again I appreciate the figures that blend in with the rest of your Substack!

I really like what you said:

> A purely linear view of time is exhausting. There is a perpetual sense of forward motion, with no rest.

I really feel like this is something that meditation has helped me with. It has given me the capacity to stop trying to keep up and just rest.

The cyclic model has some good defendants from a mathematical perspective. In a cambridge princeton cooperation a cycling model od the universe has ben proposed: https://www.edge.org/3rd_culture/turok07/turok07_index.html

https://arxiv.org/pdf/hep-th/0111030.pdf