Three Degrees of Freedom

We don't get to choose reality, but at least we get to choose our view of it.

I’ve lived many lives over the course of my thirty-odd years.

I grew up a God-fearing Catholic. I saw people through the lens of good and evil, as allies and enemies.

After leaving the Church and getting an engineering degree, I saw the world as a sort of clockwork set in motion by the big bang. People became mechanistic automata, with no free will or culpability.

And lately the the world feels animated by a life force I can neither name nor describe. I’m often struck by the stark impression that we’re 8 billion manifestations of the same underlying deity.

In fact, I’ve gotten wildly lost in the space that separates all these worldviews. Most people will change their core beliefs once or twice in a lifetime, if at all. But my interest in meditation, my use of psychedelics, and perhaps a predisposition to psychosis, have tossed me about on the sea of ideas.

Fortunately, in all that chaos, I’ve learned to navigate effectively. And there are three main levers I’ve found—three ways of modulating my worldview to make it kinder, happier, and more stable.

Outline

The Penrose Trinity

Ontology

Epistemology

Metaphysics

Pluralism: The Meta-Worldview

The Penrose Trinity

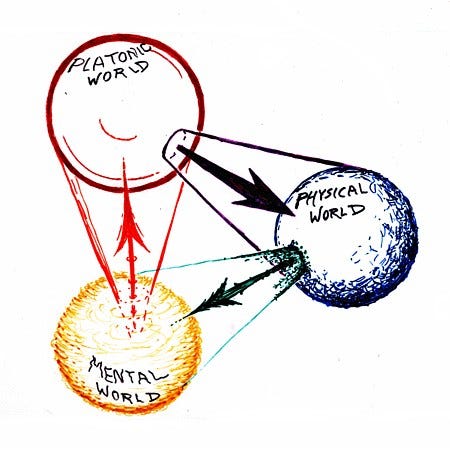

One of my favorite models of reality comes from physicist and Nobel laureate Roger Penrose:

I like to call this the Penrose Trinity. It points to three mutually arising aspects of reality:

The physical world of atoms and planets, matter and energy, space and time

The mental world of colors and sounds, feelings and emotions, impressions and dreams

The platonic world of numbers and words, concepts and logic, definitions and theorems

Incidentally, there are three intimidatingly big words1 that get thrown around by philosophers, which map neatly to the components in Penrose’s Trinity:

Metaphysics: what, ultimately, is the nature of reality?

Epistemology: where does our knowledge of reality come from?

Ontology: how do we break the whole of reality down into smaller concepts and categories?

These questions keep me awake at night. They are unanswerable, and yet they demand answers.

More importantly, the answers we adopt—even provisionally—have a huge impact on our thoughts, emotions, and behavior. Each one represents a choice, a degree of freedom in our worldview.

Ontology

Language is a tricky thing.

With words, we draw lines on top of reality. Every word lumps certain things together, and divides them from their surroundings.

An ontology uses words to break a continuous space into discrete buckets. So the full spectrum of color becomes red-orange-yellow-green-blue-purple; the vast space of musical sound gets shunted into a dozen or so genres; the interconnected web of life is split into individual species along often-debatable lines.

Of course, we can always keep zooming in, adding more categories to our ontology, capturing ever deeper levels of nuance. We can distinguish different greens like “chartreuse” and “lime”, or divide the musical world into thousands of subgenres. But no matter how small we make the divisions, behind every category sits further nuance, obscured by some catch-all label we’ve invented.

Without those labels—without words—we’d be lost in a sea of ambiguity. But we quickly forget that the lines are there, and that they’ve been drawn arbitrarily.

Usually the consequences are merely silly, triggering internet debates about whether Pluto is a planet, or whether a hot dog is a sandwich. But too often the consequences are literally a matter of life and death: ontological choices decide whether your illness is covered by insurance or whether you can be drafted into the military. The lines between criminality, insanity, and mere deviance vary widely between societies (homosexuality has spent time in all three buckets). And the Nazis famously developed a rigid ontology to decide which people should be labeled “Jewish”.

Consider the concept of gender: do we insist on splitting people into two hard categories based on the shape of their genitals? Or do we acknowledge the small minority of people who find themselves outside those buckets and the larger minority that finds them stifling? The former creates less cognitive burden for most people (only two options in the “gender” dropdown!) but fails to capture the experience of millions.

What’s more, in subjective and intersubjective domains, the ontological choices we make feed back into reality, changing the world itself. Words become magnets, drawing our attention and energy towards their platonic center and away from their boundaries. We invent an esoteric category like “superhero movies”, and suddenly billions of dollars begin pouring into films of gaudily costumed vigilantes.

Sure enough, adopting new gender categories seems to be catalyzing changes in our felt sense of gender identity:

Too often we insist that our ontological choices are inherently correct. Both the two-gender and many-gender camps will insist that their categories are a biological reality, and the other is a perverse attempt to transcend or constrain nature. But all we’re doing is drawing arbitrary lines on top of an amorphous continuum. We can always redraw the lines when it suits us.2

But a change in ontology can be deeply disturbing. Having to alter the very categories of being at the roots of our worldview is so disorienting that it has its own special term: ontological shock. Consider: merely adding a few new gender categories has thrown the world into political tumult. People literally get murdered over it.

One of the greatest metacognitive skills you can develop is the ability to let go of your ontology and witness, wordlessly, the continuum of experience sitting behind it. This shift away from thinking in discrete categories is a hallmark of mystical experience (often described as “ineffable”, or unable to be put into words), and is the reason meditators put so much effort into abandoning discursive thought.

Stepping back into that wordless vantage point allows you to reconsider and reshape your ontology. Which—as we’ve seen—can radically alter your relationship with the world.

Of course, eventually you’ll need to return to the world of words. You need an ontology if you want to have anything resembling logic or communication—there’s no way to participate in society without one. You can choose a simple ontology with few categories, or a complex ontology drowning in nuance. You can choose an ontology that’s reasonably compatible with the society around you, or one that’s disruptive to the point of creating confusion. But you have to choose.

See also: Scott Alexander on Taxometrics and The Categories were Made for Man, as well as this blog on Taoist ontology.

Epistemology

Having carved up the world into discrete categories, our next question is: how do we learn more about those categories, and the relationships between them?

Sensory experience is our most immediate (and perhaps only3) source of information. Any mind comes to know its surroundings through sensation. This is why I map epistemology to Penrose’s “mental world”.

But while sense data might sit at the root of our knowledge, it’s extremely noisy. Every second, there’s a ton of information pouring into your eyes and ears that isn’t particularly relevant to your needs, and you only have so much space in your brain.

Fortunately we seem to live in a world that mostly follows predictable patterns, and we can use those patterns to filter out the noise. We build up an internal model of those patterns, and then compare our sense data to that model.

In neuropsychology, this way of coming to know the world is called predictive processing. If you have a very strong model of how the world works, but you see or hear something that contradicts that model, you’ll typically write off the contradiction as a fluke—often you won’t consciously notice it.

This is where our epistemic freedom lies: how much weight do you give to your immediate sensory data, and how much do you give to your mental model of the world? In Bayesian terminology: how strong are your priors, your preconceptions?

Strong priors make for a predictable experience, but might blind you to what’s really happening. You can become locked in place, unable to adjust as you encounter new evidence, or as the world itself evolves into a new configuration.

Weak priors, on the other hand, allow you to see the world more directly, but will subject you to a firehose of noisy data. You might start to drift around psychotically, unmoored from any stable model of the world.

It’s not unlike the tradeoff we saw in ontology, where more categories provide nuance, but at the cost of a heavier intellectual burden. Here, weak priors provide more information about reality, but again, at the cost of a heavier intellectual burden.

No coincidence then that meditation and psychedelics, in addition to melting ontological categories, also weaken priors, subjecting the experiencer to a deluge of sensory information.

This seems to be the mechanism behind the huge psychological changes that can be induced by both contemplative practice and psychedelic experience. When we let go of our existing world-model and become immersed in sensation, our models have a chance to update, to adjust themselves to all that new information.

So once again you have a choice: how strongly do you cling to your existing model of the world? Relaxing your priors can be deeply disruptive, but that’s precisely the lubricant you need if you want to move between worldviews.

Again, you’ll eventually need to re-strengthen your priors—it’s impossible to navigate the world without a model to lean on. But as you do, you might find that your old model of the world no longer quite fits. And, as we’ll see below, choosing a new model is a matter of metaphysics.

See also: Steve Lehar’s Cartoon Epistemology, Michael Titelbaum on The Problem of the Priors, Scott Alexander on Epistemic Learned Helplessness, and Andrew Gelman on The Problem with Bayes

Metaphysics

So we’ve carved up the world into categories, and we’ve got a sense for how to navigate our sensory impressions of those categories. Sure, we made some arbitrary choices along the way, but at least now we can build an accurate model of the world!

Unfortunately, we’re still flying blind. Our metaphysical situation, by definition4, is underdetermined by the data we have. We’ll never have enough evidence to know what’s going on at the meta-level.

For example, a metaphysician might ask whether our universe came into being ex nihilo, was created by a god, or is a Matrix-style simulation built to enslave humanity. All three universes would look exactly the same from the inside—from where we’re standing, there’s no way to known which one we’re in.

And so, once again, we have some freedom.

Of course, some arguments might be more or less convincing. I think it’s reasonable to assume the universe has an intelligent creator, or that it doesn’t. But the idea that it was made in seven days, only a few thousand years ago, and that dinosaur fossils were planted by the devil to convince us otherwise, seems pretty preposterous. Possible, sure! It’s consistent with the facts, in its own weird way. But it’s so oddly specific, and requires so many unwieldy assumptions, that it seems safe to dismiss out of hand.5

We also have to face the fact that there is some kind of truth to the matter. Our ontological and epistemic choices are more or less arbitrary, but a metaphysical choice runs the risk of being wrong. Either our universe was created by a higher intelligence, or it wasn’t—whether or not we’re able to prove it.

And yet, any metaphysical assertion is built on top of epistemic and ontological choices. We can wiggle our way into conjoining any metaphysical assertion with the facts just by shifting our definitions. No one can stop us from calling the laws of physics a “higher intelligence”.

So when confronted with unanswerable metaphysical questions like: are plants conscious? do humans have free will? does life have meaning?—realize that you’re welcome to answer in either direction, maybe shifting your definitions of words like “conscious” in the process.

And, above all, consider how your answer might impact your sense of well-being, or your treatment of others.

See also: Paul Feyerabend’s Farewell to Reason, William James’ A Pluralistic Universe, and this blog on Behavioral Theology.

Pluralism: The Meta-Worldview

Once, while meditating on a profound sense of guilt, the idea struck me that if I simply let Jesus into my heart, my sins would be forgiven. I did. And it was good. The guilt melted away, for the first time in years. Nearly a decade later, I still occasionally attend a nearby Unitarian church for a healthy dose of Jesus.

But I am not a Christian. Or, I am a Christian, but am also simultaneously a Buddhist, an Atheist, and a Pantheist. Or I am sometimes some of these things, and sometimes others. And sometimes I am none of them, just a cloud of being floating in the void.

The Cosmic Dancer, declares Nietzsche, does not rest heavily in a single spot, but gaily, lightly, turns and leaps from one position to another. It is possible to speak from only one point at a time, but that does not invalidate the insights of the rest.

—Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces

That might seem flaky, non-committal, or intellectually dishonest. But I’ll happily discuss the nuances of each worldview, pointing out the parts I like and where I think its limitations are. Ultimately my attitude is a reflection of pluralism—the belief that no single system of thought can ever have the final say.

I’m not claiming that pluralism is the correct worldview—only that it’s immensely useful for me personally. It helps me empathize with just about anyone, especially people whose worldviews seem particularly foreign. I’ve heard friends express incredulity that anyone could support Trump, or believe in young-earth Creationism, or assert that 9/11 was an inside job. But after taking that familiar step back into unknowing, for minutes at a time I can try on their ideas and feel the internal consistency of their beliefs.

It’s kind of scary, feeling the magnetic self-importance, self-righteousness, and obvious correctness of worldviews that I (from my current perspective) find abhorrent. Racism feels pretty good, it turns out! From the inside, you can really see how people get stuck there.

The crucial skill of the mystic is the ability to step backwards, away from knowledge and certainty, into the cloud of unknowing. It’s only from that standpoint that all your ontological, epistemic, and metaphysical assumptions are obviously assumptions, rather than justified beliefs. And upon reentry, you may find them changed, sometimes radically.

Again, this is a dangerous quest. Once your brain is in that pliant, receptive state, it becomes thirsty for a new worldview. And it will happily latch onto the circular logic that fuels any subculture. Take LSD and wander into the wrong YouTube rabbit hole, and you might not come out the other side.6

Beware of false prophets, who come to you in sheep’s clothing, but inwardly they are ravenous wolves. You will know them by their fruits. Do men gather grapes from thornbushes or figs from thistles?

—Matthew 7:15-16, New King James Version

So it’s important to repeatedly step back, and question the worldview you’ve adopted. Questioning it on the grounds of truthfulness would be silly—every worldview is true from its own perspective. Instead, you should look at the fruits: look at your sense of well-being, and at your behavior towards others. How skillfully are you able to navigate the world? Where are you falling down? And how might an adjustment to your worldview help?

There’s no ultimate destination here, no final worldview that captures the world itself. Each one provides a unique perspective. They can be more or less beautiful, more or less safe, more or less stable. But none has the final say.

We live in a pluralistic universe. That’s my worldview, at least.

I’m offering my own definitions of these words, which are not entirely in line with how they’ve been used historically. For example, the word “metaphysics” is often used more broadly, and as encompassing ontology and parts of epistemology; and ontology is often described as studying being itself rather than the semiotics of being (as I have it here).

The standard definitions are the result of centuries of blind linguistic and academic evolution. My definitions remove some of the overlap and ambiguity, in an attempt to form an orthonormal basis for discussing metacognition.

Those definitional shifts make this essay exactly the sort of exercise in ontological freedom that it advocates for.

To be fair, the many-gender camp seems to be far more aware of the meta-level game here, of the fact that gender is a continuum which we’re forced, by the nature of language, to draw lines on top of.

An interesting and often-debated question is whether there are other sources of information that are independent of sensory data—namely rational understanding. As an empiricist, I’d answer this in the negative, and say that rationality merely emerges from sensory patterns. But this is an ontological choice! It’s turtles all the way down.

Again, by my definition. See footnote #1.

See also: Russell’s Teapot and Occam’s Razor

I’m not overstating this: an otherwise intelligent friend of mine literally began wearing tin foil hats (in the discreet form of an expensive beanie) after too many indoor mushroom trips during COVID lockdowns. He continues to wear them years later.

Fantastic read, thank you! Do you recommend Feyerabend's farewell to reason?

I think the really interesting part here is how language and thought cleave things apart, when reality is actually continuous. It's almost like we need a new language that somehow doesn't do that.