Macro and Microphenomenology

How to study the dynamics of the mind

This post is part of QRI’s HEART program. You can also read it on heart.qri.org.

For centuries, physics consisted of domain-specific models for human-scale phenomena: falling objects, acoustics, the movement of the stars, and the like. Deeper questions about the origins and extent of the universe, or about its fundamental building blocks, were relegated to philosophers and theologians.

But the discovery of a general framework for mechanics gave rise to particle physics and cosmology. Science found it had the tools to explore even the largest and smallest scales of reality.

Psychology seems to be following a similar trajectory. We have a thousand models for practical phenomena, like emotions, personality types, and psychopathologies. But increasingly scientists and psychonauts are learning to study the atoms of experience, and exploring exotic corners of the mental landscape.

I see three emerging subfields in the study of mind:

Classical Psychology, which describes day-to-day phenomena using increasingly general models

Microphenomenology, which describes the building blocks of experience and their interactions

Macrophenomenology, which describes the global geometry and dynamics of phenomenological space

Classical Psychology

Most of contemporary psychology consists of small, overlapping models of mental life. These range from scientific (e.g. the diagnostic criteria in the DSM, neurochemical descriptions of psychoactive drugs), to fuzzy-but-useful (e.g. Myers-Briggs personality types, mood wheels).

This cacophony of models resembles the state of physics at the end of the Age of Enlightenment. But in 1788, Lagrange introduced a mathematical structure that encapsulated all known mechanics, unifying many disparate theories under a single principle: energy.

Could something similar happen in psychology?

The most successful attempt here is Karl Friston’s Free Energy Principle and its cousin, Predictive Coding. These frameworks try to describe a wide range of mental and behavioral phenomena with a single mathematical formalism. Scott Alexander has some interesting speculation on how the theory explains everything from optical illusions to placebos to your inability to tickle yourself; he also has deeper dives on its application to autism, schizophrenia, and depression.

These theories won’t ever replace the point-models, for the same reason no one uses the Lagrangian formalism to determine how much fuel a rocket needs. But they can provide a unifying foundation for the huge range of psychological phenomena that comprise the human experience.

And if Predictive Coding proves to be a general model for describing conscious agents, it can serve as an intuition pump as we build models for small- and large-scale phenomenology—much like the Lagrangian formulation of physics extended its domain into the quantum and cosmological scales.

Microphenomenology

…the simplest bits of immediate experience are their own others…They run into one another continuously and seem to interpenetrate. What in them is relation and what is matter related is hard to discern. You feel no one of them as inwardly simple, and no two as wholly without confluence where they touch. There is no datum so small as not to show this mystery, if mystery it be.

—William James, A Pluralistic Universe

There are two interesting questions we can’t answer by looking at phenomena through our typical, human-sized lenses:

What are the smallest atoms of conscious experience?

How do those atoms combine to create larger experiences?

Microphenomenology tries to answer these questions by examining experience in fine detail. Say you have a headache: where, precisely, is it located? is the location moving? is it more throbbing, or buzzing? at what rate, in hertz? does the frequency or amplitude change over time? how does that correlate with the level of pain?

Deep Microphenomenological study tends to happen around the zero-state of consciousness. When you concentrate on a single sensation, everything else—sound, color, emotion, thought—fades into the background, or disappears entirely. If you can focus your attention precisely enough, it becomes a microscope for the mind, shutting out everything but a tiny slice of your experience.

But “microscope” might be too strong an analogy—phenomenology has a tendency to change in response to directed attention. You might find your headache dissipates or loses its negative valence while your attention is fixed on it. Much like small-scale physics, Microphenomenology involves complicated interactions between observer and observed, and even challenges the distinction between the two.

It’s an outrageously tricky subject to study.

Tools and Techniques

The focusing of attention on moment-to-moment experience is a long-standing technique in Buddhist meditation practice, especially Vipassana (literally, “super-seeing” or “seeing into”). Traditionally, the goal is to gain insight into three universal qualities1 of all forms:

They are ephemeral

They are unstable

They have no fixed identity

As this insight deepens, meditators experience successively deeper states of consciousness (jhanas), where experience becomes subtler and more ill-defined (the final two states are described as “infinite nothingness” and “neither perception nor non-perception”). The process culminates in nirodha-samapatti, or total cessation of awareness.

For the impatient, anesthetic drugs can take you on a tour of these near-zero states of consciousness. I’ve previously reviewed my own experience with nitrous oxide; some of my conclusions rhyme with the Jamesian and Buddhist insights above. Ether and ketamine have similar effects at the right dosage. 5-MeO-DMT (not to be confused with the more common N,N-DMT) also seems to have this property of propelling users towards the zero-state, but while paradoxically maintaining intense arousal and awareness.

Preliminary Results

The most interesting phenomenon reported by Microphenomenologists is an altered or non-existent sense of self. They might lose any sense of having a body, of being separate from their sensations, or having a central locus of awareness. Phenomenological binding itself seems to break down—the aggregate, multiplicitous experience we’re used to dissolves into its individual atoms.

Deep microphenomenological investigation often steps beyond positive and negative valence, with jhana meditators describing the last five stages of dissolution as entirely equanimous. Many long-time meditators (myself included) claim that focusing attention on a painful sensation will cause its negative valence to evaporate.2 This implies that valence may be an emergent, high-order experience.

A sense of space expanding, shrinking, or losing a dimension also seems to be common.3 Some report that all points in their visual field “become the same point”, or that the notion of distance between points evaporates. This implies that spatial extent, too, is an emergent, high-order experience.

Linear time often loses meaning during microphenomenological investigations. Time manifests in short pulsing cycles, or disappears entirely. Explorers are often uncertain as to how much time has passed during their experience. This suggests that cyclic time may be a more fundamental experience than the linear time we’re used to.

Some contemporary microphenomenologists are even helping to translate traditional meditative concepts into contemporary scientific terms: Romeo Stevens has observed that most of the mental events the Buddha discusses occur very rapidly, in the 10-40hz range; Nick Cammarata and Daniel Ingram concur, claiming that tanha specifically occurs between 25 and 100 milliseconds after a stimulus (which translates precisely to 10-40hz!).

Interestingly, explorers of Microphenomenology frequently speak in terms of vibration—a strange parallel to small-scale physics, where the most popular models involve vibrating strings or fields.

Macrophenomenology

For many, the exploration of near-zero states of consciousness feels dignified, even righteous—a preparation for the inevitable experience of death. For others, it feels boring and nihilistic.

Fortunately there’s also a vast, high-dimensional space of conscious states to explore.

Macrophenomenology looks to describe the global geometry and dynamics of phenomenological space. It’s primarily concerned with extreme pleasure and pain, but also explores richly detailed sense data, self-other interactions, and esoteric beliefs. Even enumerating the dimensions of large-scale conscious experience is a Herculean task.

Tools and Techniques

Psychedelic drugs are the most obvious launchpad for explorers interested in Macrophenomenology. They tend to produce extremely esoteric states of consciousness, with rich audio-visual-tactile phenomena, strange semantic content, seemingly-intelligent entities, and psychotic beliefs.

Active dreaming is another way to break out of the constraints imposed by external reality. The physical world seems to anchor us to a small range of conscious experiences; like psychedelics, the dream world dissolves those strictures.4

There are also contemplative practices that explore the far-reaches of consciousness. Many tantric traditions, such as those of Vajrayana Buddhism or the left-handed path of Western esotericism, encourage practitioners to conjure images of hyper-violent, hyper-sexual deities and demons, and to interact with them. These traditions tend to adopt richly colored, intricate iconography, often with jarring semantic content.

Predictive Coding has a large role to play in Macrophenomenological exploration. Deeply-held beliefs exert a gravitational pull on our conscious state; weakening those priors—through drugs, dreams, or meditation—is the key to reaching escape velocity. And strategically strengthening particular priors can help anchor you to a new subspace, allowing you to explore it more thoroughly.

The real trick is not getting lost.

Preliminary Results

My favorite Macrophenomenologist is Justin Schmidt, an entomologist who bravely explored the space of pain through insect bites. In his descriptions you can see that pain isn’t simply a single dimension: it can be more or less pure, smoky or brilliant, dull or electric. This is a typical methodology: explore some subspace as deeply as possible, and start building a map.

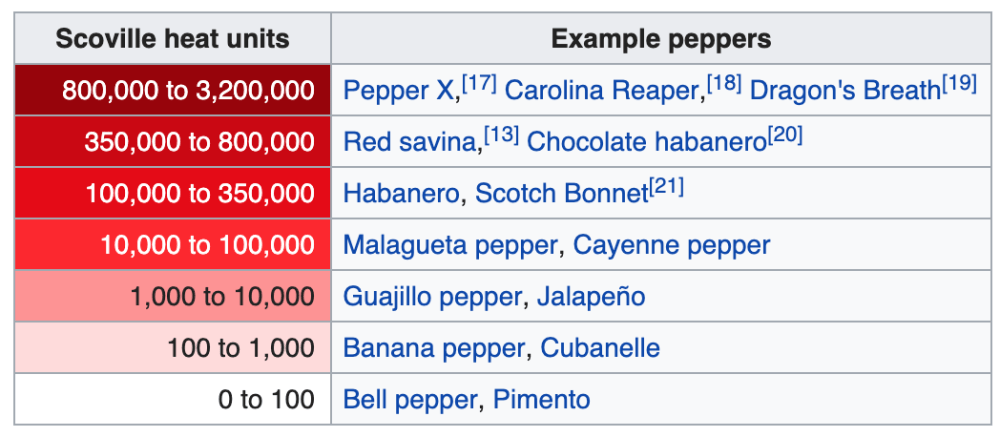

QRI has more thoroughly catalogued the space of valence, with an important observation: a fixed-sized step seems to multiply the intensity of both pain and pleasure. They cite Schmidt’s pain scale, cluster headache ratings, and the Scoville heat scale as examples of this logarithmic shape. They also provide a compelling argument that there’s a direct link between symmetry and valence.

But while pleasure and pain dominate Macrophenomenological study, the space of conscious states is much bigger than that single dimension. There’s a huge variety of high-bliss and high-suffering states, and an even bigger space of mixed states, where pleasure and pain swirl together.

Strange narratives often emerge in deep phenomenological space. Psychonauts can become possessed by the conviction that the world is ending, or that they’re a cosmic savior, or that they’ve connected to an intergalactic network of intelligent life. These beliefs are radically psychoactive, and can propel the believer into the purest dilutions of bliss, terror, and excitement (as I’ve experienced first-hand).

More progress has been made on navigational techniques than in actually mapping these spaces. Explorers like John Lilly, Robert Monroe, and Tenzin Wangyal consistently point to attention and intention as the keys to moving about in Macrophenomenological space. Whatever you focus your attention on will tend to grow, and your perceived environment will tend reflect your interior state. It’s easy to slip into feedback loops of both fear and joy.

In another strange parallel with physics, Macrophenomenology involves complicated geometry—much like Minkowski spacetime. High-dimensional and hyperbolic simulations are often reminiscent of the dream world; objects change shape, pop in and out of existence, and bend at the edges of the visual field. QRI has argued that psychedelic visuals typically have fractal properties and hyperbolic geometry; this likely has to do with the specifics of our visual processing system.

Limitations

I don’t want to push the parallels with physics too hard, or over-reify the distinction between Micro and Macrophenomenology.

The Macro and Micro scales of experience bleed into each other in strange ways, and there are plenty of experiences that seem to transcend the distinction. There are far-out, high-dimensional psychedelic experiences with low information content (e.g. 5-MeO seems to reduce the dimensionality of experience while simultaneously generating a huge amount of arousal and valence). And anyone who’s able to remember their nightly descent through hypnagogia and NREM sleep (before they enter full-blown REM) can attest to the fact that even these near-zero states can be full of emotion and semantic content.

Eventually we’ll have to contend with the fact that both small- and large-scale phenomena belong to the same continuum of conscious states. But before we jump to a theory of everything, a divide-and-conquer approach seems fruitful. We can deal with the phenomenological equivalent of quantum gravity later.

Better phenomenological theories can help us reduce extreme suffering, and to access states with strong positive valence. The more we’re able to understand how qualia arise at the smallest levels, and how to navigate the massive space of macro conscious states, the more capable we’ll be of avoiding suffering and finding joy.

But to make progress we’ll need more people—especially people with scientific and mathematical training—to explore these spaces, build maps, and report back.

There’s a technical distinction here between sankhara (form, conditioned things) and dhamma (phenomena, conditioned or unconditioned things). According to the Pali canon, the first two qualities apply to sankhara, the third to dhamma. But as best I can tell sankhara is a proper subset of dhamma, so all three apply to sankhara.

The classic formula here is: suffering = pain * resistance. Zero-out resistance (i.e. by giving the pain your undivided attention), and there is no suffering.

Worth noting, I’ve heard meditators and psychonauts describe their experience in three, two, and zero dimensions, but never one.

Worth noting, there are also dream practices that explore the near-zero states of Microphenomenology. See The Tibetan Yogas of Dream and Sleep for more.

Very interesting stuff. I'm quite new to this so would appreciate some clarity - what's the difference between macro and microphenomenology and qualia? are macro/micro both types of qualia?

Great stuff! I’m inspired to dive deeper into the qri heart program after this. Very inspiring

One small comment on “Many long-time meditators (myself included) claim that focusing attention on a painful sensation will cause its negative valence to evaporate.2 This implies that valence may be an emergent, high-order experience.” - I’m not sure it implies this, more that when you’re concentrating, there’s no self sense to create the tension and suffering (as you point out in the footnote). I still think the tension that leads to suffering may be a fundamentally valenced thing when appearing in consciousness. So valence remains fundamental, but is related to conscious tension (contraction or asymmetry)