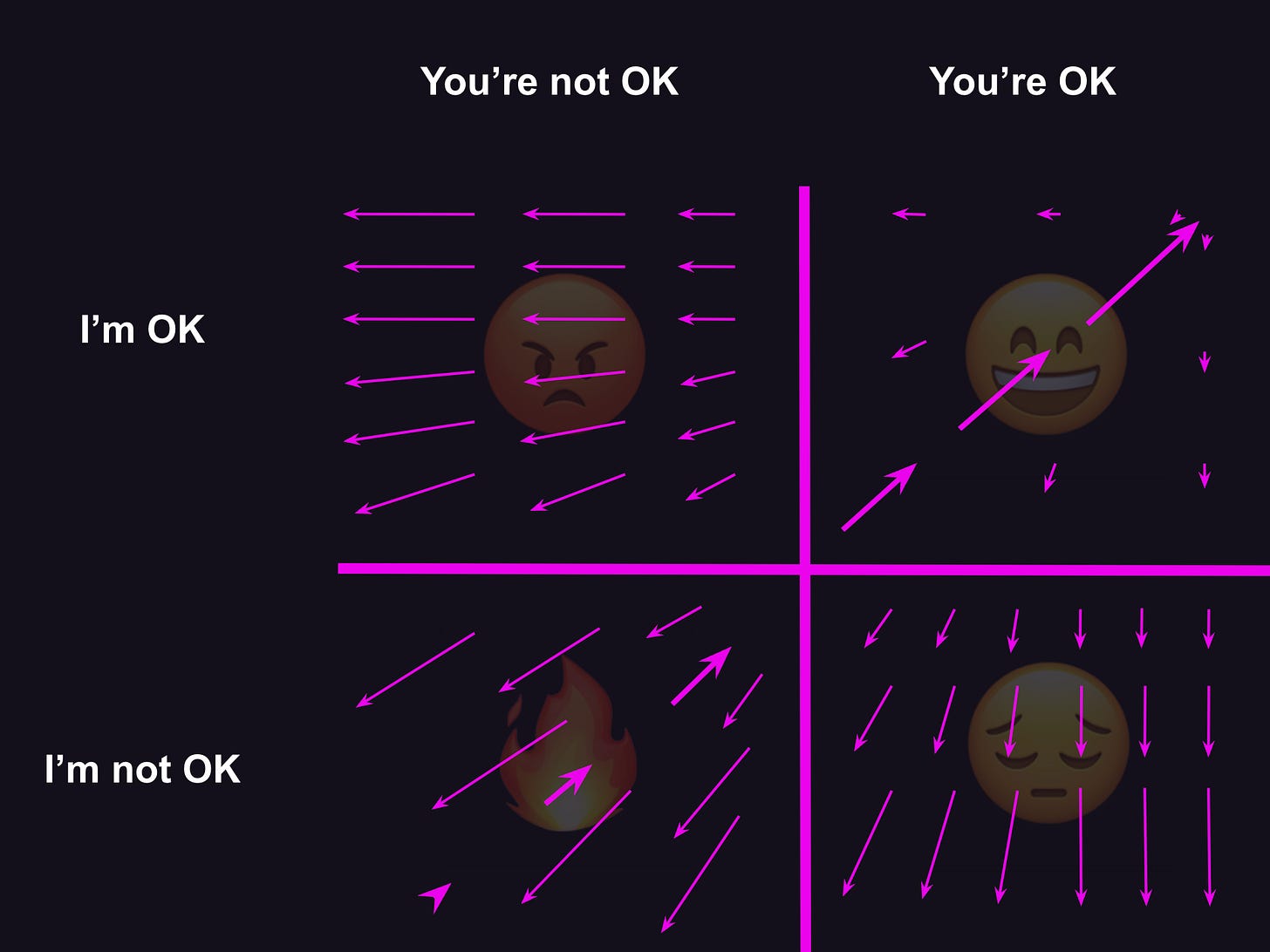

Ask yourself two questions:

How do I feel about myself?

How do I feel about others?

The answers place you somewhere1 on this grid:

Obviously this isn’t the only way to organize mental states.2 But it’s one I find very helpful.

I spend a lot of time in the right half of this map, trending upwards. But I drift around too, like a leaf on a busy lake. Every day, I spend at least a few seconds in each box. And once or twice I’ve been sucked into an eddy in that bottom-left quadrant.

Obviously we all want to be at the top-right. So what’s stopping us?

Outline

Fluid Dynamics

Feelings come and go like clouds in a windy sky.

—Thich Nhat Hang

We might drift around this map, but the drift isn’t entirely random. There are prevailing winds, predictable currents of flow. We might try to will ourselves in a certain direction, but some movements are easier than others.

In particular, it seems much easier to move leftward or downward into not-Okayness, than to move upward and rightward into Okayness.3

I can make myself angry—all it takes is a few minutes thinking about my least favorite politician. I fill my attention with Bad People doing Bad Things, and that delicious self-righteous fury starts to boil up.

And I can easily trigger a sense of shame—all I need to do is pull up one of a dozen memories (you know the ones). This is where I tend to get stuck. I start to ruminate, deliberately pushing myself further and further downward.

In fact, the further I delve into anger or shame4, the easier it gets to keep going in that direction. Like a fire that’s already raging, all I have to do is keep adding fuel.

Moving in the opposite directions is harder. I can remind myself of my accomplishments, or repeat positive affirmations, and maybe I push upwards a bit. But mostly it rings hollow—especially if I’m starting from a shame-hole.

Or I can try to push rightward through loving-kindness (metta) meditation. This works reasonably well for me in the moment, but the largest effects are short-lived. And I imagine that, for some people, metta meditation rings as hollow as positive affirmations do for me.

It seems there’s a natural drift, leftward and downward. Which makes sense—if the natural drift were up and right, we’d all be living in a John Lennon song.

This is not an optimistic picture.

But there must be something missing. Even if we’re not living in the heaven of Imagine, we’re not collectively in hell either.

I’m more OK, You’re more OK

Here’s another way of looking at our map:

There are only two sections now, determined by your self-other orientation. Above the sloping line, I feel like I’m more OK than you, even if I’d put us both in the “not OK” bucket; below the line, I’m more focused on my own shortcomings than on yours. Above the line is a sense of superiority; below it, a sense of inferiority.

I suspect most people have a stable bias toward one side of this line or the other. But we all shift positions depending on what’s in focus—I’m below the line when talking to my boss, above it when scolding my dog.

And then there’s the line itself, splitting the two halves. At these points, the “I’m OK” score is exactly equal to the “You’re OK” score. Maybe you think we’re both OK, or maybe that we both need to change. But along this line, neither side dominates—you see yourself and the people around you as equals.

This is a good place to be.

Let’s call this line (drumroll…) The Path of Equanimity™

The Path of Equanimity

Here’s a claim: along the Path of Equanimity, there’s a natural drift upward and rightward.

This is something I’ve repeatedly verified for myself. No matter how badly I feel, if I can find that balance—if I can stop thinking of myself as better or worse than the world outside me—then I slowly drift back to a place of contentment.

And I’ve come across at least one small study that replicates my finding:

For most participants [n=154], self-compassion [“I’m OK”] was positively associated with other-compassion [“You’re OK”]. However, there was substantial heterogeneity in this effect. The degree of self-other harmony [i.e. proximity to the Path of Equanimity] moderated the link between compassion directed towards self or other and well-being. Higher levels of compassion were associated with higher levels of well-being, but only for those who experienced the harmony. When the two forms of compassion were not in harmony, levels of self/other-compassion were largely unrelated to well-being.

So for subjects whose self-compassion and other-compassion were correlated, more compassion meant higher well-being. But for subjects with a low self-other correlation, more compassion was uncorrelated with well-being.

Translating that into our vocabulary5: The study found that for people on The Path of Equanimity, more compassion leads to greater well-being—moving upward tends to move them rightward, and vice versa. But for subjects with an imbalance, who live above or below the Path, more compassion was uncorrelated with well-being. They drift aimlessly around our map.

(Importantly, the study found moderate correlation6 between “I’m OK” feelings and “You’re OK” feelings. It seems many people do live on or near the Path of Equanimity, which explains why we’re not all constantly miserable.)

So no matter where you are on our map, if you can find your way to the Path of Equanimity, you’re on your way home to that top-right quadrant.

And it’s not hard to get there if you know the terrain.

Two Paths

With a bit of willpower, I can move myself around Okayness-space. But, as we saw, it’s easiest to move left and down into anger and shame. Deliberately moving up and right is a struggle—except on the Path of Equanimity. So how do we get there?

Here’s the good news: no matter where you are, you can find your way to the Path of Equanimity just by moving leftward or downward.

In other words: shame and anger counteract one another. If you’re feeling ashamed or inadequate, a little anger can stir you out of it. And if you’re angry, a little self-reproach can ground you back into balance.

Again, this is something I’ve repeatedly validated. When I’m being swallowed by feelings of shame and inadequacy, I can wrap myself in a cloak of spite, and drift back into a happy equanimity—after a short detour through hell. Conversely, it took a great humbling for me to end my foray into manic narcissism (as well as a much longer stay in that bottom-left quadrant).

It’s important not to overshoot! You can end up stuck in the opposite extreme, or vacillating in circles around the Path of Equanimity. There’s a ton of psychological research on shame-anger loops: anger arises as a way of avoiding shame, and the resulting outburst leads right back into shame. With each turn of the loop, you cross that point of balance, but momentum prevents you from escaping.

If you’re operating consciously, it’s you can manage the risk. For me, it only takes a pinch of anger/spite/disdain to escape the shame hole. Or if I’m upset at someone else, all it takes is a few seconds of ruminating on some of the stupid shit I’ve done. Suddenly I’m back to feeling even with the world—and then begins the slow drift into a comfortable Okayness.

Both these paths have been traced by others as well.

The Leftward Path of Anger

There’s broad agreement that anger is a natural coping mechanism for shame—often it’s seen as a symptom of hidden shame. And half a century ago, it was common advice to “vent” your anger—picture the frustrated analysand being encouraged to “hit the pillow.”

Research has since shown that venting tends to make angry people angrier—just as we’d expect from our map—so it’s fallen out of favor as a universal salve. But for those of us who live below the Path of Equanimity, a moderate amount of anger can be immensely helpful. It shifts our focus from inward problems to outward problems, breaking us out of habitual self-reproach, stirring us into action.

Nothing annihilates an inhibition as irresistibly as anger does…destruction pure and simple is its essence. This is what makes it so invaluable an ally of every other passion.

To a Fox, a Garibaldi, a General Booth, a John Brown, a Louise Michel, a Bradlaugh, the obstacles omnipotent over those around them are as if non-existent.…many have the wish to live for similar ideals, and only the adequate degree of inhibition-quenching fury is lacking.

—William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience (links mine, obviously)

Or, for a more contemporary example, Sabaa Tahir speaks of rage as a vehicle for escaping a sense of powerlessness:

Rage can fuel you. But grief gnaws at you slow, a termite nibbling at your soul until you're a whisper of what you used to be.

—Sabaa Tahir, All My Rage

My favorite example is Camus: instead of rage, he advises scorn. Camus spent years grappling with the profound insignificance of humanity, which should have placed him squarely in the bottom-right quadrant. But he describes Sisyphus—a former king cast down into the underworld to be a “futile laborer”—finding his way back to happiness not by elevating himself, but by lowering the gods:

Sisyphus, proletarian of the gods, powerless and rebellious, knows the whole extent of his wretched condition: it is what he thinks of during his descent. The lucidity that was to constitute his torture at the same time crowns his victory. There is no fate that cannot be surmounted by scorn.

…Sisyphus teaches the higher fidelity that negates the gods…One must imagine Sisyphus happy.

—Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus (emphasis mine)

The Downward Path of Shame

On the other side of our map, we have the reverse situation: an excess of anger, hatred, or narcissism calls for a dose of shame.

This downward path pops up most often in religious contexts: self-effacing practices, like vows of poverty and silence, are common for monastics seeking enlightenment; Aldous Huxley believed ego-reduction was the key to all religious feeling; and William James’ Varieties of Religious Experience is full of anecdotes from people who found lasting happiness only after accepting their own wretchedness and submitting to a higher power.

Here’s one of the stories James collected, from a reformed alcoholic (emphasis mine):

I took too much and came home drunk. My poor sister was heart-broken; and I felt ashamed of myself and got to my bedroom at once…About midday I made on my knees the first prayer before God for twenty years. I did not ask to be forgiven; I felt that was no good, for I would be sure to fall again. Well, what did I do? I committed myself to him in the profoundest belief that my individuality was going to be destroyed, that he would take all from me, and I was willing. In such a surrender lies the secret of a holy life. From that hour drink has had no terrors for me: I never touch it, never want it…Since I gave up to God all ownership in my own life, he has guided me in a thousand ways, and has opened my path in a way almost incredible to those who do not enjoy the blessing of a truly surrendered life.

In Psychology, shame is typically seen as something to be overcome, rather than as an asset. But it does serve its purpose! It prevents us from drifting too far off into “I’m OK, You’re not OK” territory, keeping us grounded in common decency and social norms.

Unless one feels shame to some extent, one cannot emerge successfully from any well-worn pathologic behavior pattern.

—Henry P. Ward, Shame: A Necessity for Growth in Therapy

For someone who lashes out at the world, or has narcissistic tendencies, or is stuck in that mode of self-righteousness that pervades every political subculture, shame is an immensely useful anchor.

Breaking the Cycle

Of course, it’s best if we can just stay on the Path, avoiding anger and shame altogether. And with practice, this does seem to be possible.

Horace Fletcher tells of a conversation with a friend who had taken up Buddhist meditation:

…I longed to taste some of the sweets of the calm he pictured, and begged him to tell me the process of the discipline, so that perchance I might follow it and reap some of the benefits.

…“You must first get rid of anger and worry.” “But,” said I, “is that possible?” “Yes,” replied he; “it is possible to the Japanese, and ought to be possible to us.”

…From the instant I realized that these cancer spots of worry and anger were removable, they left me. With the discovery of their weakness they were exorcised. From that time life has had an entirely different aspect.

—Horace Fletcher, Menticulture

For me, the process hasn’t been quite as short or as simple. But the more I balance my self-other orientation, feeling neither superior nor inferior to the world, the more I escape that natural current pulling me into shame, anger, and despair.

In fact, as I discovered during a minor bout with depression last year, I can escape those feelings entirely during meditation. I just sit, find my way to the Path of Equanimity, and float home. More and more, that feeling is becoming stable, something I can carry with me into daily life.

Again, the key is a balance of self-other orientation. If you feel superior, you’ll spend your time swimming in anger and disdain; if you feel inferior, you’ll be mired in shame and anxiety. But if you can balance the two, if you can “love your neighbor as yourself”, you’ll float equanimously toward happiness.

But if you ever find yourself out of balance, a touch of the opposite affliction can get you back on track.

Okayness, here, is a belief that something needs to change. The more you feel “I’m not OK,” the more desperately you want to change yourself. The more you feel “You’re not OK,” the more you want to change other people, or maybe the world at large.

Okayness is related to valence—your sense of pleasure and well-being—but they’re not the same thing. Okayness is really a synonym for equanimity, an acceptance of things as they are. You might be having a high-valence blast at a party/concert/orgy, but if you’re craving and clinging to that enjoyment, afraid of losing it, you’re not entirely OK. Or you could have a severe headache, but if you’re not resisting the pain, you’re still pretty OK.

This diagram was popularized in the 60s self-help book I’m OK, You’re OK. I haven’t read it, only lifted its main idea and made it my own. I have no clue as to how much the ideas here resemble the original text.

Holding external stimuli constant, that is. It’s easy to push yourself around the grid by taking drugs, spending time with different people, etc. But we can only control our external environment so far. And after any external change, we tend to revert to baseline.

Throughout this essay, I’m going to use “anger” as shorthand for all the “I’m OK, You’re not OK” feelings, like pity, disgust, and narcissism. Ditto for “shame”.

I’m making a few assumptions in my translation here:

Self-compassion is the same as a high “I’m OK” score, i.e. upwardness

Other-compassion is the same as a high “You’re OK” score, i.e. rightwardness

Well-being is the same as high self- and other-compassion, a measure of how up-and-right versus down-and-left you are. This isn’t the definition used in the study, and is the biggest leap I make.

A score of 0.39 (where 1.0 is perfect correlation, and -1.0 is perfect inverse correlation)

Wonderful post. Such a clear exposition of something that, I think, many of us are dimly aware of. Thank you!

I absolutely love the gropings towards complexity theory here. You never actually say the word 'attractor,' but your vector fields are so suggestive.

One of my favorite online essays. Pretty old, but still useful.

http://www.davidbrin.com/nonfiction/addiction.html